Freelance miners dig for raw jade at a company site in Hpakant, Myanmar, in 2018.Hkun Lat

The jade gemstones that generate billions of dollars a year in Myanmar — the world’s biggest exporter of the stone — are beloved in China, where they can sell for more than gold. But they are a symbol of tragedy and suffering for the people who live and work in the country’s mines in Hpakant, in Myanmar’s northernmost Kachin State.

Lahtaw Kai Ring, a former jade miner and a mother of six, recalls what the area was like when she first moved to the township in 1989. The Uru Stream was clean and clear, and people harvested a freshwater oyster — called n-hypa law in the local Jinghpaw language — in its waters.

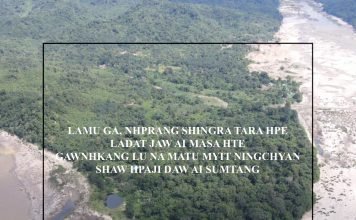

“Now [people] don’t even know what n-hypa law is,” she says — they don’t see that oyster in the stream anymore. “Hpakant’s environment is destroyed. Mountains became valleys and valleys became mountains. Rivers, streams and creeks are upside-down, shifted into chaos.”

This year, on July 2, a landslide underscored residents’ concerns. The side of a mining site collapsed, sending a torrent of mud and rainwater into the mining valley below. It killed nearly 200 people, mostly freelance miners searching for jade stones while companies had ceased operations for the rainy season. This tragedy is just one of the many deadly environmental disasters that have happened in the jade-rich township after two decades of intensive mining.