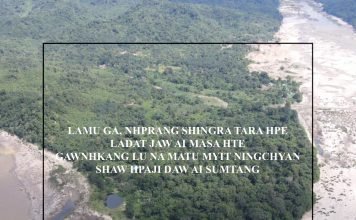

The anticipated cancellation of the controversial China-backed dam in Kachin State would be an opportunity to build trust with civil society and move forward with smaller hydropower projects in other areas of the country.

By JOERN KRISTENSEN | FRONTIER

AFTER MORE than five years of uncertainty, it seems likely that the Myitsone Dam will be cancelled.

Such a decision would create a rare opportunity for dialogue between government and civil society on how best to produce and distribute electricity for economic development in Myanmar, including hydropower. This opportunity should not be lost.

Damming Myanmar rivers remains controversial. This was demonstrated yet again when the International Finance Corporation, a member of the World Bank Group, conducted public consultations in Kachin and Kayah States in late January and early February to inform and receive feedback on a planned Strategic Environmental Assessment of hydropower in the country. People gathered outside the meeting venue to express opposition.

But tensions remain high on both sides. At a recent press briefing, the permanent secretary of the Ministry of Electricity and Energy, U Htein Lwin, expressed frustration at the government’s inability to move forward on new hydropower projects due to public opposition.

Given the legacy of hydropower in Myanmar, the lack of acceptance from the public is understandable. In the past, during years of military rule, the approach has not been strategic; the aim was to maximise profit. Developers were allowed to choose sites for construction of hydropower dams with apparently little consideration for environmental and social safeguards. Communities that would be affected by construction, including those being relocated from villages where they had lived for generations, were not consulted. There was no dialogue.

This lack of regard for people’s feelings, traditions, livelihoods and human rights – particularly in ethnic areas, where most dams were planned – led to strong opposition to the Myitsone and to several dams that would be built on the Thanlwin (Salween) River. Ethnic communities, suffering from decades of armed conflicts and social exclusion, would have none of the government’s plans.

The fact that large proportions of the electricity was meant for neighbouring countries and not to power Myanmar – let alone local communities where the electricity was being generated – just made opposition to the dams even stronger.

At the same time, it is indisputable that Myanmar needs electricity for its development.

“With electricity comes job creation. People will have opportunities to create their own jobs with their own business. It will also enable places where electricity is available to attract investments. We must therefore accord priority to electrification in line with job creation,” State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi said in her address to mark the first anniversary of the National League for Democracy government.

Finding a way out of the dilemma between a desire for economic development and the fierce rejection by civil society of using the country’s rivers to produce electrical power is both fundamentally simple and overwhelming complex. It is about building trust.

When taking office in 2011, President U Thein Sein’s government found itself confronted with the same problem that has plagued Myanmar throughout its history: lack of trust between the various ethnic groups residing in the periphery, and the Bamar majority living in the central part of the country. It persist today under the NLD government. Distrust is at the root of the armed conflicts. And it is broadly understood that trust needs to be built before there can be any meaningful discussion of how to achieve economic and social development for – including how to proceed with the electrification of the country.

Cancellation of the Myitsone Dam would mark an important step in trust building. If followed quickly by several actions, it could help break the deadlock and open a constructive dialogue between government and civil society.

This would require a number of government initiatives. These include:

1) Suspend any current plans to build major dams on the Ayeyarwady and Thanlwin mainstreams. Declare that priority will be given to medium and small dams on tributaries if they meet all requirements for environmental and social safeguards. Such action will be in line with recommendations issued by World Commission on Dams in 2000.

2) Upgrade existing hydropower plants and complete ongoing projects to maximise output of electricity in the short term.

3) Plan electrification based on a mix of energy sources. Myanmar is rich in coal, gas, hydropower and biomass, so has a wide range of options. Prioritise wind power in coastal regions and solar power in the dry zone – these technologies are not just environmentally friendly, but increasingly competitive on cost.

4) Promote a strategy to establish regional and local distribution networks to provide electricity to households not connected to the national grid and unlikely to become so in the foreseeable future. Negotiated in an open and transparent manner, such an initiative can support the peace process.

5) Present the result of the IFC Strategic Environmental Assessment at public consultations across the country, including ethnic states. The SEA can serve as a neutral guide to dialogue and decisions on the role and place of hydropower in comparison with other options for producing the power Myanmar so desperately needs.

Hydropower has a negative reputation in many countries, not only Myanmar. But not all hydropower dams are the same. And there are examples where this renewable energy is being produced and used in a way where the benefits outweigh any costs.

In Norway, a country with among the highest standards for social equality and environmental protection in the world, the entire population enjoys access to electricity generated by hydropower. Conflicts over the location of dams have been much reduced since the country developed a comprehensive master plan in the 1980s, to decide which projects were in the public interest and which rivers should be protected. Today the population of Norway enjoys high standards of living and Norwegians were recently ranked as the happiest people in the world.

However, if not well planned, dams could have a number of significant and negative impacts – not least on fisheries and agriculture and, in turn, the livelihoods of rural people. Proper environmental and social impact assessments – where it is the responsibility of the developers to prove no harm – and public consultations and dialogue must be undertaken before final decisions are made on building any dams.