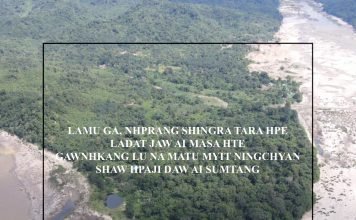

On June 5, Myanmar Army helicopters dropped leaflets over parts of Tanai in western Kachin State, ordering residents to leave by June 15 or risk being “considered as cooperating with the terrorist group KIA [Kachin Independence Army].”

Soon after, the Myanmar Army, or Tatmadaw, launched offensives against the KIA in the amber and gold-rich area. The build-up and fighting forced thousands of local and domestic migrants who had been working there for years to flee; many of the displaced are now staying at temporary shelters provided by churches in Tanai town.

Then, on August 4, military representative Maj Hlaing Phyu proposed in the Kachin State parliament making Tanai (also known locally as Hukawng) an environmentally protected area, an anti-mining indictment that would essentially drive the KIA from the territory. He argued the KIA had benefited through taxes from illegal mining whereas the state government had lost revenues. His proposal was rejected, however, after receiving 20 votes for and 29 against.

Ten days later, Tatmadaw representatives assigned to Parliament reiterated its policy to protect the resource-rich territory in Tanai and attack the KIA in line with the 2008 Constitution—without need for approval from the government, they said.

The region they are contesting—Tanai—is rich with natural resources, including lucrative pieces of amber resin, some of which comprise extraordinary treasures such as a dinosaur-era cockroach and a 100-million-year-old damselfly.

A Curse

Jade, gold, amber, timber, and iron can all be salvaged in Kachin, potentially generating millions of dollars. Are these natural resources a blessing? Of course, if they are properly managed.

Regrettably, Kachin is faced with what scholars call the “resource curse,” an abundance of natural riches that draw trouble rather than advantage. In essence, countries with great natural resources tend to be more impoverished—or at least to grow more slowly—than resource-poor countries. Kachin proves the theory: people live in abject poverty among a land of profitable reserves.

In Hpakant Township, for example, where millions of dollars worth of jade has been unearthed, locals are denied direct access to mining because large companies control the plots.

A 2015 Global Witness investigation reported that the families of senior military figures Than Shwe, Maung Maung Thein and Ohn Myint hold multiple concessions on jade production which between them generated pre-tax sales of US$220 million at the 2014 jade emporium (the official government jade sale), and US$67 million at the 2013 emporium.

Likewise, many gold, amber, iron mines, and logging enterprises are under the control of joint ventures, militias, the Border Guard Force (BGF), and ethnic armed groups. Arguably, only people who are linked with these groups can benefit from natural resource extraction. Many locals of these areas sell vegetables, work in fisheries, and hunt for their livelihoods.

Ceasefire Capitalism

Kachin has several armed groups, including the Tatmadaw, KIA and its political wing the Kachin Independence Organization, as well as a BGF, and militia groups Lasang Aung Wah and Danggu Dang, also known as the Rebellion Resistance Force. There is also a militia of ethnic Lisu, and the Red Shan (Shanni) Army. The groups are all believed to hold business assets—particularly involving natural resource extraction—in their territories.

During the ceasefire era, the military regime allowed ethnic armed groups to do business, an act leading to so-called “ceasefire capitalism.” Northern Command commanders wielding considerable power selectively dispensed licenses, permits and business opportunities.

The KIO ran the business conglomerate the Buga Company Limited, which allegedly bought Namti sugar factory from the military government for an estimated 200 million kyats (US$150,000) according to Hpauwung Tang Gun, former Administration Officer of Namti Sugar Factory.

Other armed groups like the National Democratic Army-Kachin (NDAK), which formed into the BGF in 2009, reportedly extracted molybdenum in Pangwah, and militia groups such as Lasang Aung Wah and Danggu Dang reportedly logged timber.

The leaders of these groups were co-opted into new patronage networks exploiting the natural resources of land they controlled with the help of Chinese businessmen, according to the 2014 Journal of Contemporary Asia’s “The Political Economy of Myanmar’s Transition” by Lee Jones.

Economic Institutions

Economic institutions shape the incentives of key actors in society. They not only determine the collective growth of an economy, but also how the pie is divided among different groups and individuals, now and in the future.

Natural resources should, of course, be distributed equally among citizens, and not just benefit so-called “cronies,” military generals, militias, armed groups and the BGF.

Without economic institutions, a country may face what is called “rentier effects” in which the state derives a substantial portion of its revenues from the rent of indigenous resources to external clients. The revenues reduce the need for the government to tax the population, which may hinder the development of a representative political system.

Low-taxed citizens may then soften on holding the government to account, in turn decreasing the pressure to improve the quality of an institution. In a nutshell, when the government raises taxes, citizens demand more accountability.

Economic institutions must manage the allocation of natural resources. But effective institutions are not possible in the vast territories of Myanmar without a federalist system that ensures equal rights and opportunities.

Therefore, the Tatmadaw’s clearance operations against the KIA in order to control resource-laden land will fail to bring additional revenues to the state without effective institutions. Instead, they will lead to further casualties and produce more displaced people that nobody wants to help anymore.

Joe Kumbun is the pseudonym of a Kachin State-based analyst.